Posted by Allan Wilson on the 31st August, 2021

I’m using my retirement from the role of Information Officer with CALL Scotland at the end of this month as an excuse to reflect on some of the changes that have taken place in assistive technology and augmentative and alternative communication, and the role of CALL Scotland over the past 30 years.

I started working with the CALL Centre, as it was then known, on 18th October 1993. CALL then stood for “Communication Aids for Language and Learning” and we were located in a basement at the back of Buccleuch Place, as part of The University of Edinburgh’s Department of Education. The windows were covered with metal grids and were level with the car exhausts in the car park behind us, so ventilation wasn't great. It wasn’t the best working environment – a cleaner used to call it the Coal Cellar, and I could definitely see where she was coming from with this description, though there wasn’t any coal in the building at the time.

CALL’s Changing Focus

During the mid 1990s CALL was gradually transitioning from a model based on individual projects, each attracting their own funding, to becoming a national centre providing services to schools, with funding from the Scottish Office / Government. Much of CALL’s early work is summarised in “25 years of CALL, 1983 – 2008”, but I must mention Paul Nisbet’s pioneering work developing early versions of many of the adapters that allow people with disabilities to access technology, leading ultimately to the Smart Wheelchair, and Sally Millar’s development of Personal Communication Passports as an empowering means for people with communication difficulties to provide information about themselves. Various forms of Passports are now used throughout the world, but very few people know that they arose from Sally’s work in the early 1990s.

In 1993 CALL provided Assessment / Support for 19 individuals, 12 children in schools and 7 adults. Visual impairment was the main difficulty for three of the children while the others had complex multiple difficulties, including communication difficulties. In our latest reporting year, 2020-21, 40 pupils were referred to CALL by local authorities for assessment and support, while 209 pupils from 24 local authorities received some level of support from CALL.

There is a similar contrast between 1993 and 2021 with regard to training. In 1993 we provided one two-day course in a school, organised three seminars and helped to organise two conferences. In 2020-21 we ran 45 individual courses, attended by 1,000 teachers, therapists, parents and others, and hosted 21 webinars, seen by over 10,000 people either live, or via archived recordings. We also gave 12 conference presentations and hosted our own ASL and Technology virtual conference.

Assistive Technology in 1993

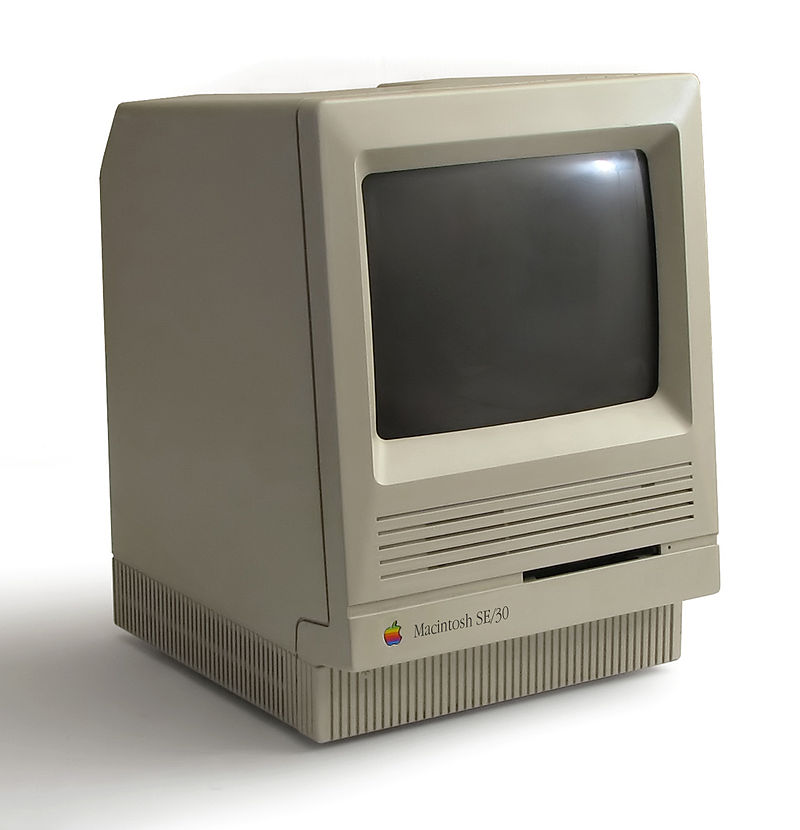

In 1993 we mainly used Apple Mac computers for work, though we also had a couple of PCs, an Acorn Archimedes and some BBCs. I used an Apple Mac SE30, with a rather unusual second display designed to fit an A4 page. In theory, it could be rotated for use with portrait and landscape pages, but the driver had not kept up with changes to the Mac operating system so it only worked in portrait mode. Many schools were still using BBC computers, while Macs were popular in Scotland, and the Archimedes in other parts of the UK. Under pressure from corporate IT services in local authorities, PCs were beginning to appear in schools.

The main focus of the CALL Loan Bank when I started was on electronic communication aids. There were two main categories: digital speech devices, which relied upon somebody recording messages (e.g. the IntroTalker and the MessageMate) and synthetic speech devices containing a speech chip which could convert text into spoken words, albeit with a robotic voice (e.g. the Toby Churchill Lightwriter SL30) and the Liberator). There were also ‘hybrid’ devices such as the Mardis ORAC, which included both digital and synthetic speech. Digital speech generally sounded ‘better’ and provided almost instant access to the phrases that had been stored in it, but the user was restricted to using somebody else’s words Synthetic speech allowed the user to use the full richness of language, but it could take a long time to compose a message. There were none of the popular single message devices that later became important for early learning – the BIGmack was only released in 1995.

If you want to know more about some of the communication aids available in the 1990s, the December 1998 issue of the Communication Matters journal provides an excellent overview.

We also had a broad range of switches to allow people with physical disabilities to access these communication aids, and a range of interfaces that allowed switches to be connected to a computer to provide alternative access for people who could not use a keyboard.

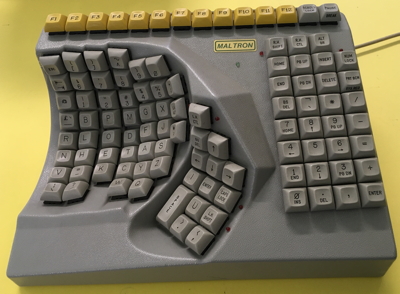

There were alternative keyboards for people who struggled to use a standard keyboard, but they were generally very expensive. Maltron, for example produced a range of ergonomic / single-handed / head stick keyboards, which are still available. The Maltron single-handed keyboard cost £295 in 1993 and still costs exactly the same!

For people who struggled to control a mouse, there were probably more trackballs and joysticks available in 1993 than there are today, but, again, they were expensive. It was also possible to add a touch screen to a standard monitor, or to get a touch monitor which had a touch sensitive surface. These devices are still used in EPOS systems and public information screens, but are rarely used in schools where tablets have become the norm.

When it came to text-to-speech software to support reading / writing difficulties in 1993, the Mac and the Archimedes had built-in sound, but they both needed specialist software to provide text-to-speech (Write:OutLoud / Co:Writer for Mac, Talking TextEase for the Archimedes). PC users would have to wait until the introduction of the Windows 95. People requiring text-to-speech support for a PC would need to buy an external speech synthesiser.

Speech recognition software was available for the PC in the form of Dragon Dictate, which I first saw in 1992, a year before my official start at CALL, when I sat in on a demonstration by Peter Kelway from Aptech. I was working to set up CALL’s database systems at the time. Dragon required the user to – speak – one – word – at – a – time, but could be pretty effective, provided that mis-recognised words were always corrected. This process of correcting the text allowed some atypical, e.g. dysarthric speech to be recognised. Sadly, later developments in more natural, continuous speech recognition became less useful for people with atypical speech. A recent CALL webinar by Richard Cave on Speech recognition for communication impairments demonstrated some current research in this area.

Enquiries and Desktop Publishing

So, what was I doing at CALL back in 1993? There were two main aspects to the Information Officer role at the time: responding to enquiries and desktop publishing.

Enquiries generally came by phone or letter. (As a centre within The University of Edinburgh we had individual email addresses and we managed to negotiate the use of a generic call.centre@ed.ac.uk address, but hardly anybody else had email at the time.) When it came to responding to enquiries, the internet was in its infancy with no Google and no web sites with a focus on assistive technology or augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). (When the first CALL web site was set up in 1996, an Alta Vista (1990s equivalent to Google) search revealed that it was one of only six across the world that referenced augmentative and alternative communication.) In Sally Millar, Paul Nisbet and Stuart Aitken I had access to three of the UKs leading experts in AAC and AT, while CALL had accumulated a substantial library of books and journals. In my early days, I relied heavily on the expertise of my colleagues and access to this library in my response to enquiries. Typical enquiries were along the lines of:

- I’m a school pupil doing a project on Computers and Disability – can you help (i.e. can you write my essay for me)? I wouldn’t write the essay, but I would send bullet points on the main points to consider along with photocopies of individual journal articles, extracts from supplier catalogues, etc. (The British Computer Society’s Ability journal and Closing the Gap were often helpful, as was the Disability Information Trust’s Communication and Access to Computer Technology)

- I’m a speech and language therapy student, interested in AAC – can you send me any information? I would advise them of information in journals such as ISAAC’s AAC, Communication Matters (for which I did the desktop publishing for some time) and Communication Outlook, and if they couldn’t access them, I would send copies of individual articles. This initial response often led to further dialogue. Years later, I would have an occasional conversation at the Communication Matters conference with a specialist SLT who would reveal that my response had helped to spark an interest in a career in AAC.

- I’m a teacher with a pupil who struggles to use a standard keyboard – do you have any suggestions? I would try to identify the source of the difficulties and try to make suggestions. Would a bigger / smaller keyboard, or a keyguard help. If an alternative keyboard might help, I would offer a loan of one or two keyboards to try. What about changing accessibility settings? Would word prediction or speech recognition help? I would talk through these options and send further information if required.

- My child has cerebral palsy and struggles to speak clearly. Can you help? I would probably pass this on to Sally Millar, but would ask about involvement with local speech and language therapy services, particularly if she had been in touch with the relevant specialist centre. If Sally was not available. I would also talk briefly about the potential use of different AAC devices, but making it clear that I could not provide formal advice.

A year before I started at CALL there had been a move away from formal project reports to the production of ‘proper’ books with ISBNs, resulting in:

- Accelerated Writing for People with Disabilities by Sally Millar and Paul Nisbet. This looked at how word prediction and other computer software could be used to make typing less tiring, particularly for people with physical disability.

- Augmentative Communication in Practice: Scotland. Collected Papers: Study Day 1992 by Helen Galloway and Sally Millar, bringing together the 13 papers presented at the 1992 ACiP:S Study Day.

I took on the desktop publishing role and also arranged printing and marketing for the publications, and over time began to contribute content to some of the publications. These included:

- Collected Papers for many further Augmentative Communication in Practice: Scotland Study Days, including 1998’s Augmentative Communication in Practice: An Introduction, which became recommended reading on AAC for university courses.

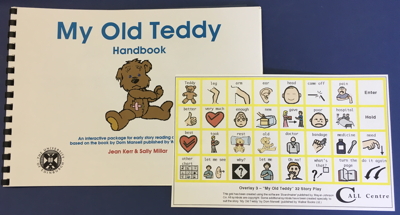

- My Old Teddy, an interactive story reading pack for the Mardis ORAC communication aid, based on Dom Mansell’s book of the same name. This was an early example of CALL’s work on using symbols to support early literacy, which would eventually lead to our work the Scottish Book Trust to create symbolised resources for their Bookbug books. See our Symbols for All site for more about this and other symbolised resources.

- Supportive Writing Technology, which illustrated a trend to a broader definition of Communication to include support for reading and writing, rather than just speech and language, leading to fruitful collaborations with Dyslexia Scotland and more advice and support for learners with dyslexia and other literacy difficulties. Coinciding with the 25th anniversary of our creation, we changed our name from CALL Centre to CALL Scotland, with CALL now standing for Communication Access, Literacy and Learning. (We also wanted to escape from endless emails and phone calls offering CALL Centre training for our staff.)

- Personal Communication Passports, Sally’s magnum opus on Passports.

Over time, my role in desktop publishing decreased, but I would like to mention my downloadable iPad Apps for Learners with Dyslexia poster, first published in 2013, and regularly updated to become our most frequently downloaded resource, with over 175,000 downloads since it was created. This makes no allowance for the local authorities and others who have downloaded the poster to share with colleagues. The popularity of this and the other iPad posters reflects one of the most significant developments in assistive technology in schools, the growing impact of iPads in education.

This has been my last (and longest!) blog for the CALL web site. I hope it has been of interest to a few people.

Our social media sites - YouTube, Twitter and Facebook